Before DNA proof-of-parentage became possible, practical things were different in many ways, Ben Reach and Sam Nixon MD contemplated in their end-of-day musings over drams of The Macallan in Ben’s library-conference room. Nowadays, proof of “who’s your pappy?” was answerable conclusively by a Q-tip swab of saliva submitted to a lab test for humans or beasts, thanks to DNA science.

This had revolutionized pointing dog breeding practices starting in summer 2003 when the Field Dog Stud Book, registration authority for pointing dog trial dogs in North America, imposed a requirement for DNA proof-of-parentage for recognizing placements in Championship events. Since then, the simple certification of parentage by owners of sires and dams has not sufficed for proof of bird dog parentage.

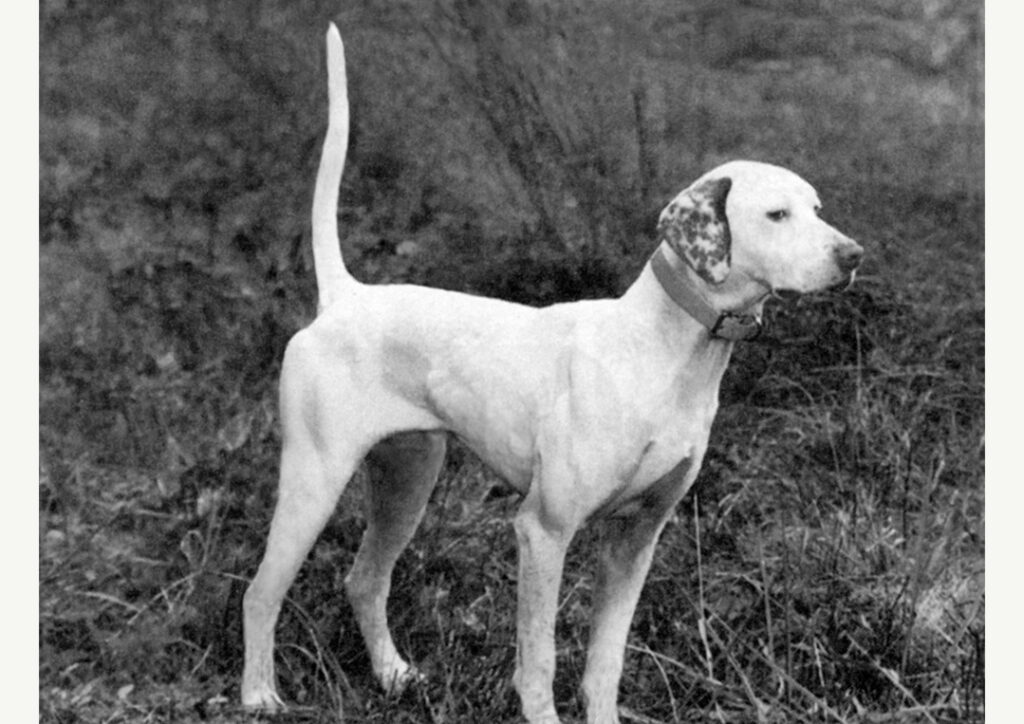

Soon after the rule was announced, following the 2004 National Bird Dog Championship, the FDSB used findings of alleged earlier misrepresentation of parentage brought to light by DNA evidence in Draconian fashion, banning certain persons (including a Hall of Fame member) from participation in trials. The AFTCA followed suit. And two leading stud dogs owned by the banned Hall of Fame member were in effect declared dead (in the fashion of certain Jewish parents for a child wedding a gentile) for competing or breeding purposes. Thus the sport of field trials lost its best living sire, based on winner production, Miller’s White Powder.

But today Ben and Sam were contemplating earlier days. Ben said, “In the old days, a handler could get a little boost in income from stud fees.”

Sam said, “Didn’t the owner get the stud fees?”

“Oh no,” Ben said, “by custom the handler got all or most of stud fees, and for a very practical reason.”

“Why,” Doc asked.

“Think about it,” Ben said. “The stud dog was with the handler. Getting the female bred was a lot of work and trouble. Especially if the handler was on the road or away from home at trials, it was easy to say, ‘not possible.’

“So the smart owners said to the handler, ‘You get the stud fees’ (or most of them).

“Then there was another game some handler’s played. Breed the stud dog, take a reduced fee in cash, let the female’s owner or handler claim a stud he owned was the sire on the registration papers.”

“Did that really happen?” Doc said.

“Oh yes. There are crooks in all walks of life. DNA discovery and the DNA rule in bird dog breeding were a very good thing.” Ben said.

“Did they eliminate all the cheating,” Doc asked.

“Oh, no. The birthday cheating still goes on,” Ben said.

“What the hell is that?” Doc asked, as he poured them dividends of the Macallan. “And let me tell you about how DNA technology has changed my medical practice.”

* * * * *

“Tell me how DNA has changed your medical practice,” Ben asked Doc when their drams of The Macallan were refreshed.

“Where do I start,” Doc began.

“More times than I can count, a female patient has said to me, ‘I want to have another child, but not with my husband. I am staying with him, because I do not believe in divorce (or cannot afford divorce). But I want my child to have a better daddy (smarter, kinder, whatever). If I do, can my husband prove it?’

“Before DNA was discovered, I could say, ‘not likely’. But after DNA’s discovery, I have had to explain that if you ever get divorced, no matter who initiates it, there will be DNA testing of your children for paternity. My big problems have been with women who asked me the question before DNAs discovery and I answered ‘not likely’ and they ask now again after DNA discovery.”

“My, that is a problem for you,” Ben said, and poured Sam a dividend of The Macallan.