It was a desperate year by every measure. The Great Depression had refused to end; war threatened again in Europe as Germany, now under Hitler’s thumb, smoldered with resentment under the punishing terms of the Treaty of Versailles; and most Americans lived in poverty, those rural who had no debt the best off because they could at least grow and put up their own food for winter and darn their threadbare garments and socks.

There was some comfort in the fact almost everyone else, save a small sliver of the populace (Ford and Chevy dealers, undertakers, small-town movie theater owners) which had somehow escaped the wrenching poverty of the 1930s, was also desperately poor and in the same boat.

Still, bird dog field trials had survived, if barely. Maybe because in hard times men clung to bird dogs with desperate affection. Still that tiny cadre of professional trainer-handlers that followed the circuit hung on by their toenails, save the few who were privately employed by one (or occasionally two or three) very rich men.

As February and the National Bird Dog Championship approached, two dogs had emerged as favorites. Ironically they were littermates, brother and sister, pointers. Alabama Al, handled by Vince Blain, private trainer-handler for multimillionaire James Cory, owner of coal mines in Pennsylvania and a thirty-thousand-acre pine, cotton and quail plantation in west Alabama, and Georgia Peach, owned by his handler Barney Griff (a bequest from one of his few remaining patrons who had died of a heart attack at Christmas, no doubt brought on by the stress of the impending failure of his haberdashery in Atlanta).

On the Saturday night of the National’s drawing at the hotel in Grand Junction, Barney had borrowed Peach’s entry fee from a fellow handler, giving his handling horse as collateral. He and his scout Willie Blevins were camped in tents on a farm near the Ames Plantation on land owned through foreclosure by a bank and grown up in weeds, hoping against eviction. Fortunately Willie was a good hand with a skillet and they had found fresh eggs laid by hens abandoned by the foreclosed owner.

Al and Peach drew the last brace as bracemates. The weather on the last day proved ideal. Birds were moving and the littermates traded errorless finds through two and a half hours, after which they were tied at ten each. Their races were comparable, all at the front and deep but not too for Judge Ames’ standard.

Then birds shut off. The bracemates hunted their course on opposite edges and at the call of time both were gone out the front. The judges halted and behind them the gallery. Handlers and scouts rode ahead searching, desperate to show their dog to the judges who had given them thirty minutes to do it. Everyone sensed one of the two would get the title, but gallery opinions were split about even on which.

The minutes ticked away. At 28 after time the call of point was relayed in from far ahead. Despite their contrary rule, the judges cantered. A scout mounted with hat raised appeared ahead in pines. It was Willie, but the dog pointing was Alabama Al, not his Georgia Peach.

Peach was found by a plantation hand an hour later. Alabama Al was named National Champion. Barney led his horse to the truck of the handler who had lent him Peach’s entry fee.

After pictures were taken on the front steps of the manor house, James Cory asked to speak privately to Barney Griff. Barney asked his scout Willie to join him for the conversation. Barney expected James Cory to tip Willie $5 or $10 for his good sportmanship.

Instead James Cory said, “Barney I want to offer you the job of manager of my Alabama plantation. You and Willie will train and manage my hunting string and run the hunts. And I’ll buy Peach from you for whatever in reason you think she is worth.”

Barney and Willie accepted the offer. Barney then said, “I’ll take for Peach what you think she’s worth.” Then he asked Cory for an advance and redeemed his handling horse.

Three years later Barney was drafted and served in the infantry in Europe. Willie joined the Army Air Force and became a Tuskegee Airman, his extraordinary eyesight gaining him admission and metals.

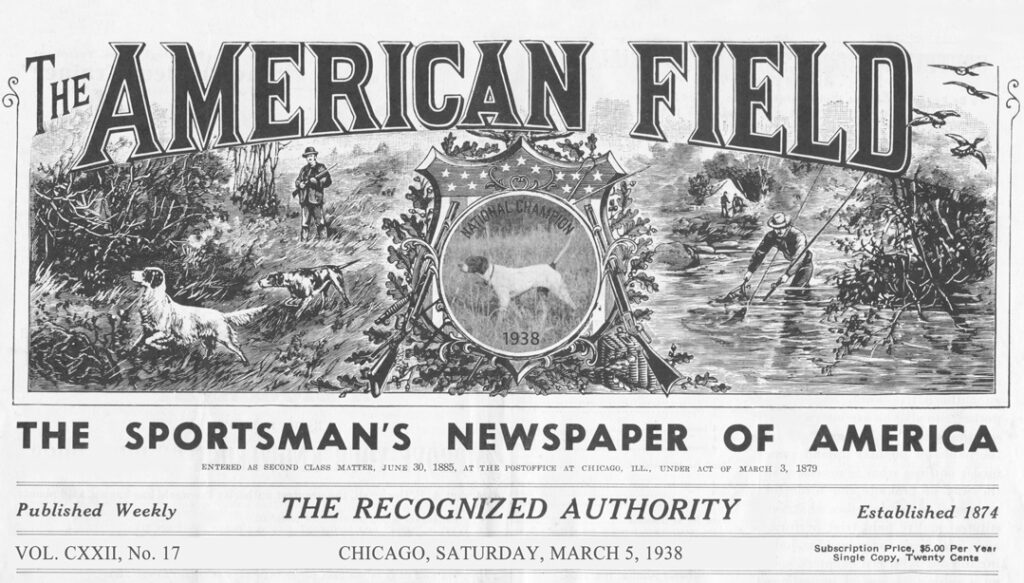

Author’s Note: this story and the accompanying cover image of the March 5, 1938 issue of The American Field are fiction; the National was not run in 1938.