In the summer of 1973, when I was thirty-five and a striving Richmond lawyer, I got an amazing gift from a more striving life insurance salesman hoping for referrals from me, an introduction to his brother, Joe Prince, perhaps Virginia’s most striving grain farmer, and after his crops of wheat, peanuts, soybeans and corn were up, most striving quail hunter.

Joe Prince, then forty-four, a veteran of WWII and a confirmed bachelor, lived with his widowed mother Mizz Grace beside the Seaboard Railway mainline in the village of Stony Creek, Virginia, twenty-four miles south of Petersburg. Once home to four cotton gins, Stony Creek was then a sleepy crossroads supporting two hundred retired or commuter residents and a few outlying farmers with a small grocery, a state liquor store, a community bank branch office and a pharmacy, plus a hardware-feed-and-seed store and post office.

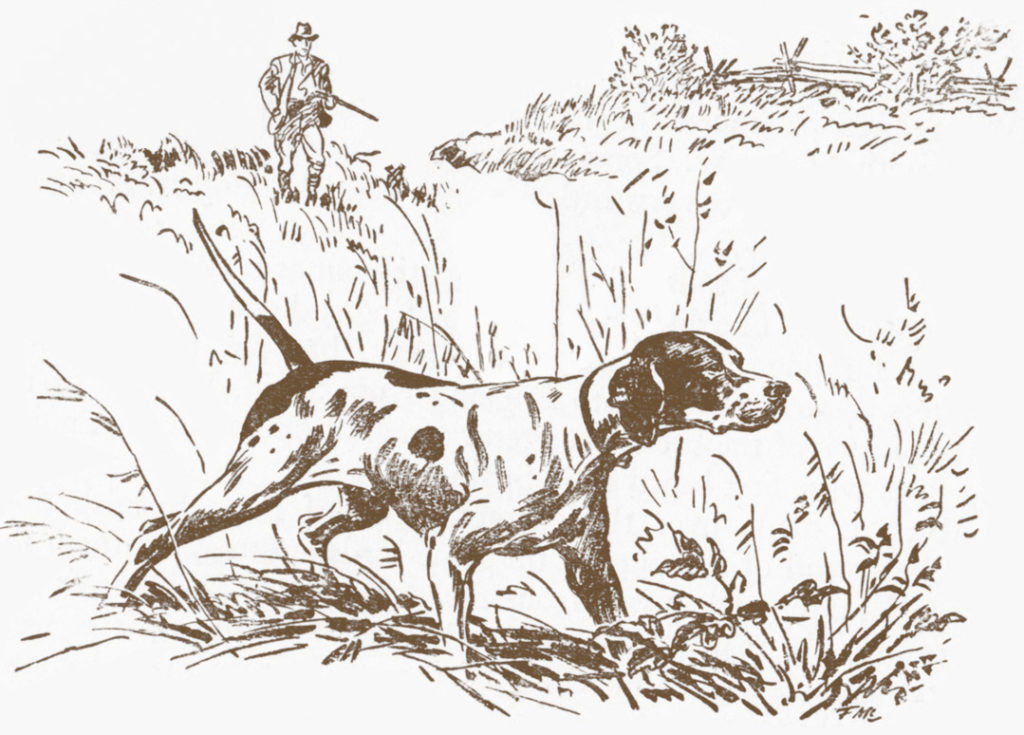

Joe was widely known as an avid quail hunter. Close beside his residence stood a four-run kennel holding a dozen level-tailed pointers of all ages, all descended from a male Joe acquired as a pup in the 1950s from a legendary dog jockey named Perkins from Zions Cross Roads. Joe had stopped at Perkins’ Kennel out of curiosity to inspect the inmates while on a spring livestock buying trip. The pup later named Lucky was accidentally let out of a run by Joe and lit out for the horizons, unheeding to Perkins’ calls of “come here.”

The pup was perhaps four months old with a black marked head, thin and obviously wormy. He had likely had no human attention since weaning and little before. But something about him caught Joe’s attention. As the pup ran free over the large hay field adjoining the kennel, Perkins tried to interest Joe in another inmate of the fifty-odd in his inventory, but Joe’s interest kept returning to the black-marked pup running free, zipping from corner to corner.

“How much for that pup? Joe finally asked.

In frustration, Perkins blurted “50 bucks.”

Joe turned his attention to catching the pup, never saying “I’ll take him.”

Finally, perhaps a half half-hour later, Joe managed to maneuver the pup into a woven wire fence corner and catch him. Walking to Perkins at the kennel with the squirming pup under his arm, he again asked “How much?”

In frustration, Perkins said, “Just take him. If he works out send me $50.”

Joe loved a bargain and a challenge. He thanked Perkins and placed the pup in a crate in the two-ton cattle truck whose stake bed also held a half-dozen restless feeder calves. When in three hours he reached Stony Creek, he found the pup slobbering with motion sickness.

Joe wormed the pup, then put the crate, pup inside, in the shade neared his kennel and slipped in pans of water and dry dog food. Then he turned to caring for his new calves. Next morning Joe opened the door to the pup’s crate and watched it streak for a distant field edge and follow it out of sight. The food was uneaten.

Through the summer, the pup ran free, returning to the crate unseen, Joe assumed in the night, to eat food Joe left there for him. Occasionally Joe saw him in the daytime at a distance, always in motion, apparently self-hunting for game, whether quail, song birds, ground hogs or rabbits, Joe could not tell. Somehow he avoided being hit by an auto or train.

Fall arrived and Joe began the harvest, starting with digging and shocking peanuts, then combining soybeans and corn. When quail season opening arrived, Joe began daily hunts, loading a couple pointers from his kennel in a box in his pickup after giving a half-dozen hands marching orders for the day. The pup watched from a distance. Joe ignored him.

About mid-season the pup one morning came to the tailgate of the pickup and when Joe opened the dog box the pup jumped in and curled up as far from the door as he could get. Joe ignored him and added companions from the kennel. At Joe’s first stop to hunt the pup jumped out and began to circle the harvested bean field which adjoined a cutover. Three hundred yards out he pointed on the edge and Joe walked swiftly to him. Half way, the pup ran his covey up, chasing with glee. Five minutes later he repeated the point-run ‘em up routine. Returning to the truck and calling in the brace-mate, the pup came in and followed it into the dog box.

Joe did not allow the pup out of the truck box the rest of the day. For the rest of the season Joe took the pup each day and gave it a chance sometime during the day. It inevitably found birds ahead of its brace-mate and after pointing them briefly ran them up.

Last day of the season arrived and Joe took only the pup. His regular hunting companion in those days, Frank Slade, a neighboring farmer like Joe, accompanied Joe and the pup. Joe attached a long check cord for the pup to drag, hoping to be able to get close enough to the pup to step on it before the pup ran up its birds, but the pup figured out the rope’s length and never let Joe or Frank get close enough to step on the rope.

Through the day the pup, dragging the rope, found and ran up birds. As the magic moment arrived (that time shortly before dusk when the temperature drops, air turns over, and dogs sense scenting conditions have improved and perk up) Joe decided on drastic measures.

Loading his Remington auto loader with skeet shot, he watched for a moment and distance when he could shoot the pup in the rear just as it moved to run up its birds, sting it but do it no lasting harm. By the time darkness ended the day’s hunt, the pup was broke. It proved to be a natural, soft-mouthed retriever. It never again bumped, much less ran up, a bird.

Up to now, the pup had no name, being called just “Pup.” On the drive home Joe said,

“We need to name the Pup.”

Frank Slade said without hesitation, “Lucky.”

“Why?” Joe replied.

“Cause he is lucky to be alive, considering dodging cars, trucks and Seaboard trains and considering how many times you shot him today.”

So the Pup became Lucky. For the next twelve years he hunted every day of quail season for Joe and his companions. More significantly, he sired each year several litters of pups, from Joe’s bitches and those of others who observed or heard of his bird finding prowess. Joe never bothered to get his registration papers from Mr. Perkins so never knew his breeding, but based on his drive and style he was clearly close to field trial stock, likely from the Fast Delivery line, widely used by trialers and hunters in Virginia and the Carolinas at the time.

The day I arrived at Joe’s home for my first quail hunt, in November 1973, Joe had in his truck’s dog box just one dog, a large white and black pointer I learned was King, the last surviving son of Lucky. Joe drove to a nearby bean field and released King, who promptly ran to a honeysuckle patch at the field’s edge and pointed with eleven o’clock style. When the covey erupted Joe shot once and dropped a bird (I shot twice and missed). King had watched Joe’s bird fall and retrieved it to Joe without command.

“How old is King” I asked.

“Seventeen,” said Joe. “From Ole Lucky’s last litter.”

From that day until Joe’s death in 1997 I would quail hunt with Joe one or two days a week during the seasons. Those days kept me sane. I never saw Lucky, but I hunted over many of his descendants. According to Joe and Denny Poole, Joe’s other regular hunting companion and mine, those descendants had many of Ole Lucky’s peculiarities, about which you can read more in later chapters of this story.

Joe never answered my question, repeated every season, “Did you ever send Perkins $50 for Ole Lucky?”

Good ern. You inspire me.

I have a story something on that order about Oklahoma s Mark A son of Easy Mark.

GREAT READ….

Great story!