Like all old bird hunters, I have stored in memory a book of the lives and deaths of the bird dogs which owned my heart over six decades. Most came to me as weanlings, lived with me an average of twelve years, and passed into eternity moistened by my tears. Ben, one of the best, came to me at his age eighteen months, and as one of but a few pointers.

A year before, I bought as a weaning his littermate sister whom I named Jill, and later gave to my pal (later a judge) Sam Kerr of Appomattox, for whom she became a star. How I bought Ben is a story in itself, which I will tell here as an introduction to our years together.

Lee Rhodes was a retired tradesman of Warsaw, Virginia, on the Northern Neck, a long narrow peninsula between the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers. Lee occupied his free time raising and starting a litter each year from a good dam and sire of the Wariel line that he also handled in weekend fun trials, numerous in Virginia in those days (the 70s).

A year after buying Jill, I returned to Lee Rhodes’ home at Warsaw to buy a pup for my hunting partner, Joe Prince, who had admired Jill. When Lee came out of his house to greet me he had at his side the dog that would become my Ben. He was handsome, high tailed and high headed with a liver mask reminding of over-sized aviator sun glasses. Lee told him to stay with me and walked into his back yard. There he hid a red handkerchief under bushes. Returning to me in his front yard, he said, “Fetch, Ben.” Ben took off like a shot for the back yard and in less than a minute returned with the red handkerchief clutched in his mouth and brought it to Lee. Lee hid it again and again Ben retrieved it. (I would use Ben’s performance of this act for years to entertain children and win bets from doubting adults).

I asked about Ben’s history. He was a littermate of my Jill whom Lee had sold as a country-broke derby. The buyer had promptly taken Ben to a shooting preserve and shot over his head repeatedly with a Twelve Gauge, rendering him gun-shy. Lee had taken him back and rehabilitated him. He was now a favorite of Lee’s

I asked how much to which Lee replied, “Not for sale.” I knew that meant, “It will take a high offer.” Ten minutes later I wrote Lee a check for the gift pup for Joe Prince and for Ben. The amount was more than I had in the bank. I stopped at a phone booth and called my banker for a loan to cover. Asked for what purpose I answered, “A household emergency.”

I took Ben straight to my Vet for a health check. He called next day to give me bad news. Ben had heart worms. I authorized the dread arsenic treatment. Ben survived it.

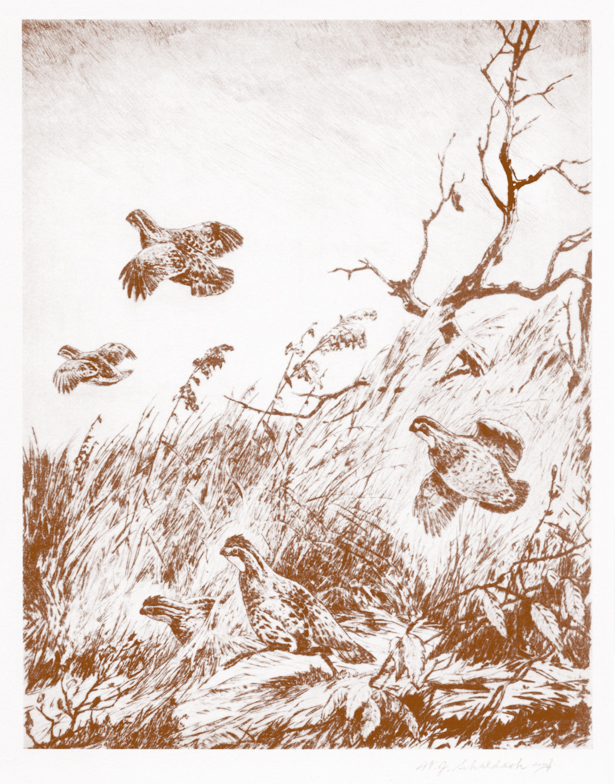

As summer turned to fall I began to condition my dogs for hunting season. Ben regained his strength and proved wide but biddable. He loved big open spaces, casting down wind on the edge of the biggest field to its end, then turning across the front and returning to me along the opposite edge. When soy beans were harvested this proved his signature move in the bean-peanut-loblolly pine country of Sussex County. I can see him now whipping into point on a distant edge, remaining high-tailed and rigid until we walked to him. A covey would burst from cutover cover before him and shots would erupt from he barrels of Joe’s and Denny’s Remington autoloaders. No sign of gun shyness ever revealed itself in Ben.

Ben was an excellent retriever, sure and quick on dead birds or runners and tender mouthed. (Joe could not abide a hard mouthed dog.) Ben was good after singles as well as coveys, willingly obeying the “hunt close” command even when distant objectives temped him to seek another covey. He backed without caution and without flagging.

Ben’s specialty was roading a covey running to roost through cutover or big woods late in the day. He knew just how close he could crowd them and never flushed them. In our country they tended to run to a swamp edge, then pitch over water to a hummock of high ground in the swamp. “Get ready, they are going to jump” I can hear Joe Prince muttering now.

Then we would hear their wing beats and sometimes get a glimpse of their flight through the pines and holly trees. Fire would erupt from Joe’s and Denny’s barrels, and they would say in unison, “Dead, Ben, dead.”

The sun would be disappearing below the horizon when we emerged from the pines and headed for the pickup, Ben making a last cast ahead of us around the edge of the bean field.

On my last hunt with Ben there were just the two of us. He was thirteen. He cast out of sight and I lost him. A half hour later when I returned to the truck he was standing by it. Deafness and cataracts had stolen his ability to orient to my whereabouts. I miss him still and enjoy our hunts in memory.