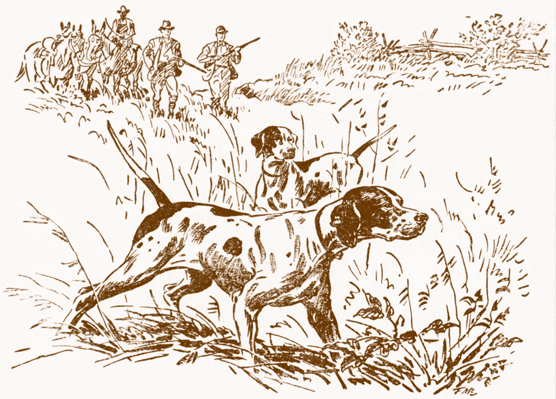

It’s the 1930s, times are desperate, the Great Depression has the world in its grip, yet for a few at the top nothing has changed. So it is for Harley Keen and Richard Bain, owners of businesses whose products are still in demand at prices producing a profit. Keen’s is tobacco, Bain’s is whiskey, legal again with Prohibition’s repeal. They are sports, and their shared passion is bird dog field trials. Each year they sponsor several dogs on the circuit, on prairies in early fall, in the Midwest In later fall, in the Deep South in winter, then in Grand Junction, Tennessee and Shukualak, Mississippi, the National Championship and National Free-For-All Championship at season’s end. Usually the National precedes the Free-For-All, but this year the order will be reversed because a winter storm has postponed the Free-For-All.

Keen owns a quail plantation in Georgia, Bain one in Alabama. Each employs a trainer-handler of his own, based at his plantation where he also supervises quail hunts for his employer and guests. They are the only white employees on the plantations. The rest are black, and paid little but provided housing, garden plots, seed, shoats, a milk cow, a mule and work in the big house or around it as gardeners, cooks, nannies, nurses, seamstresses, maids, butler, grooms, mule skinners, kennel men and field trial scouts.

The scouts are key to success in trials and hunting operations. They socialize and start the pups and retrievers and do much to finish them as well. And they are magicians with the dogs in trials, making their races the shows they must be to win the big ones, covering up their holes, assuring they appear after absences at the front and never from behind. They are the heart of the field trial game, knowledgeable fans know, but it’s the 1930s and then and for years after they are invisible in both a complimentary way (a scout should never be seen at his work) and in getting credit, where they deserved better. They are never mentioned or given credit for a dog’s performance in a written report in the Field or the Memphis Commercial Appeal. Their tips from rich owners for a win are meager at best.

This year Keen and Bain each own one dog that is a top contender for both the National and the Free-For-All titles, according to field trial gossip. This is rare, for it usually takes two different kinds of dogs to win these three hour heat trials. The National is run at a pace, set by the judges, suitable for quail hunting, and encouraging an easy handling race and dog. But the Free-For-All is run at a faster pace, also set by its judges, and encouraging a wider, faster race and dog.

When Keen and Bain went to the Canadian prairies together in September to hunt sharp tails and Huns, lodging and eating in Bain’s private rail car, they made a bet. If either man could win both the National and the Free-For-All this season with his contender, the other would pay him $100,000. It was a bet fueled by Bain’s product, made during a poker game clouded by the by-product of Keen’s.

Keen’s dog is a natural for the National, but not for the Free-For-All. She lacks the natural range and speed and flash of the Free-For-All type. But Keen’s handler Ed Moore sets about planning a strategy to win the Free-For-All with Mary Muldoon, Keen’s contender. How can he make it appear that she is sweeping the country in the Free-For-All when her natural race is a modest, honest one, along the edges and into the birds cover just ahead of her? The key, he knows, is through the artistry of his scout, Booty Blevins, who can take Mary into cover along the course and send her on casts from key points that will make Mary’s race appear to the judges as much wider and free wheeling. All fall he contemplates and discusses with Booty how they can execute this strategy at Shukualak.

Then in December the judges for the Free-For-All are announced in the Field and Ed Moore is devastated. One of the judges is known as a stickler for limiting scouting. He demands that a scout not be dispatched from the gallery without his approval. This will make his and Booty’s strategy unworkable, for it contemplates that Booty be in the woods most of the time.

Then fortune, fueled by the Great Depression, smiles. Booty comes to Ed Moore hat in hand and makes this plea.

“Mr. Ed, I got a big problem and a big favor to axe of you. My only brother lost his job in Chicago and has come here looking for work. He can live with me in my cabin. Could you maybe get Mr. Keen to put him on as a kennel man or a groom, he won’t need much pay.”

At that moment Booty’s brother appears, and Ed Moore almost faints. He is the spitting image of Booty.

“Is this your brother? He could be your twin!” Ed Moore says.

“Matter of fact, Mr. Ed, he is,” Booty says.

From this comes Ed Moore’s and Booty’s strategy to win the Free-For-All with Mary Muldoon.

Mary wins the National hands down with her usual race and ten finds, requiring little scouting.

Ten days later at Shukualak she qualifies in her hour at the Free-For-All with a far flung race in which she is seen little but always at the front in the distance and she scores two limb finds on which Ed Moore rides up on her pointed. She had been put on them by Booty riding a new black horse while his twin, posing as Mary’s scout, rides at the back of the gallery on Booty’s usual scout horse and dressed in Booty’s trademark black rain slicker.

In the three-hour finals Mary is launched on casts that appeared to the judges to be wide and forward but are in fact not deep at all, being launched by Booty from an edge where the terrain creates an optical illusion. Much of the three hours Booty is resting her at heel, waiting to take advantage of turns in the course, or a couple of times carrying her forward on the pommel of his saddle. She scores seven finds, all engineered by Booty but with Mary discovered by Ed. Early in the brace Mary’s brace-mate has been run off to the rear by Booty and declared out of judgment. Booty’s twin never leaves the gallery and when Mary is declared Champion, the scout-leery judge congratulates Ed Moore on Mary’s un-scouted race.

Harley Keen collects $100,000 from Richard Bain, a fortune in Depression dollars. Booty and his black horse were never seen scouting, and Booty’s twin brother never rode Booty’s scout horse into the woods.