The year was 1961. Mose Green had scouted for Ike Weeks thirty years. Mose was black. Ike was white. They lived mid-March through June in Southwest Georgia, but spent most of nine months of the year away, July through mid-September on Canadian prairie, the rest of the year on the road traveling to trial venues, Midwest, Southwest, finally Deep South for the cold months.

They traveled in a two-ton truck, stake body, drop tail gate, hauling horses and a string of crated pointing dogs, mostly pointers, occasionally a setter. They were always within a few days of dead broke. Then they would have a small spurt of good luck and win enough of the meager purse money to cover fuel and feed to the next trial. Or an owner would give Ike a bonus for a big win or an advance. Sometimes they found or created road kill. It went into the simmering pot for dog food.

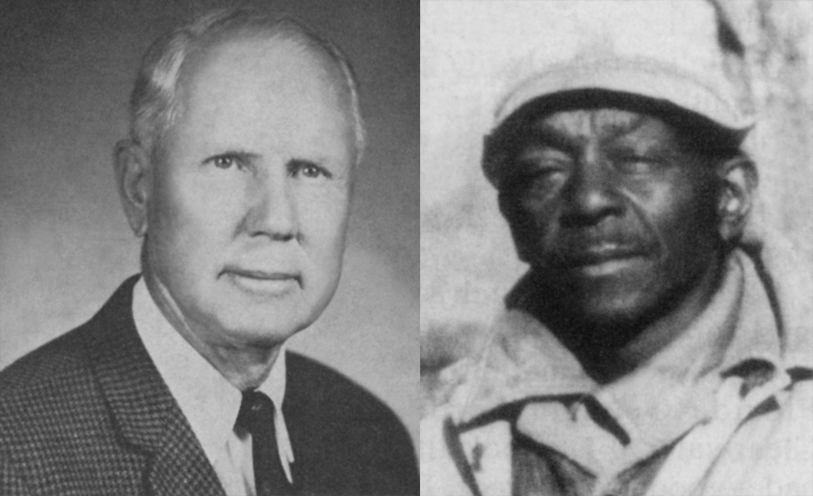

Their competitors lived pretty much the same, save for a few who trained and handled for one rich man, Clyde Morton being the prime example and the envy of the sport. He trained at Sedgefields, Mr. Sage’s place at Safford, Alabama. The Sage-Morton team had a secret weapon, a black man named Man Rand Jr.

Rand was Morton’s scout, same as Mose was for Ike. But much more than that. He started the puppies, from the day they whelped, fed and fondled and walked and talked to them every day after. He had the time for it, because Morton entered only a few trials, the big ones. And Sage had the money for the good bitches and studs, and Morton could pick them, with input from Man. Morton and Rand were the envy of all.

Sage was a purist. He founded and sponsored the Free-For-All and National Derby Championships, but ran them on neutral ground. He did so because he objected to certain things about the National Championship, where he had been a director. He respected the handlers, sponsoring a formal dinner for them at the Free-For-All where white-coated waiters served them with the manners and grace expected at the Waldorf Astoria in Sage’s New York City. Sage was that rarest of things, envied but admired.

* * *

For the first time, a third person rode in the truck between Mose and Ike on the circuit this year, Mose’s son Gus, age eighteen. Mose and Ike were getting long in the tooth. Gus was there to help with the care and feeding of the animals, to drive some when Ike wearied, and as apprentice scout to his father. The apprenticeship had begun three years before on the prairie, when Gus had made the trip there for the first time for the training season (when it ended Gus caught a ride home to Georgia with a plantation dog man).

Occasionally at a trial Ike called on Gus to scout, freeing Mose up for some chore or to ride front. As the season progressed, Gus became more and more skilled as a scout. But he had one weakness. He could find an errant dog as long as it was moving, but somehow he could not see one on point. Time after time he passed by a dog handled by Ike he was scouting. Ike grew disgusted with him and told him so.

Then at a trial in Georgia just before Christmas, where the black scouts were gathered at night to talk trash and shoot craps, Gus was noticed by Walker Lee, a scout for Big George Moreland. Big George stood just short of seven feet tall; it took a hell of a horse to carry him. Walker Lee noticed Gus was depressed.

“What’s got your goat son,” Walker Lee asked Gus.

“Mr. Ike is ‘bout to let me go,” Gus spurted.

“How come?” Walker Lee asked.

“I can’t seem to see a dog I’m scouting when it’s on point?” Gus admitted.

“Just look for something ain’t supposed to be there,” Walker Lee said.

Gus remembered Walker Lee’s advice. Next day he was scouting a dog for Ike when it entered cover on the right of the course. Gus drifted right just after the judges passed the place where the dog entered cover. Walker Lee’s words rang in his ears. He saw a splotch of white in brown blackjack leaves, like a discarded fast food bag. Looked again and saw it was his dog.

“Point!” Gus screamed. Ike and a judge arrived, and right after them Mose, who was riding front, and Walker Lee, in the gallery to be ready to scout for Big George in the next brace. They were smiling, and so too was Gus, finally. He had learned to be on the lookout for something “Not suppose to be there.”

AUTHORS NOTE: Walker Lee Clinton taught Luke Weaver to find a dog pointed when scouting with the simple advice, “Look for something ain’t supposed to be there.”

Photo: Legendary trainer/handler Clyde Morton and his famed scout Man Rand Jr.

Love these stories.

Thank you!

Awesome! Thank you for sharing!