Ames Plantation Manor House (©Ames Plantation)

He farmed, but the center of his life was judging. Judging bird dog field trials. He had judged for years. Judged all over the U. S. and in three Canadian provinces. He got more invitations than he could accept. And for the last ten years he had judged the National. Those two weeks, sometimes longer, were the highlight of his year. He was now senior judge.

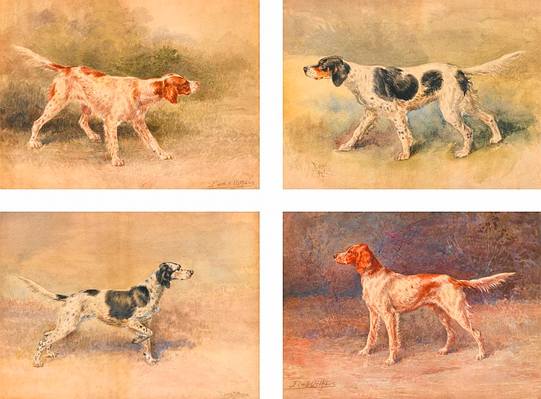

He loved staying in the Ames Manor House with its Osthaus paintings of early Setter National Champions. He had his own chair in the Gun Room. There an Osthaus drawing of Hobart Ames himself, crossing a stream on his knees on a log during a coon hunt, a batwing of bourbon in his back pocket, hung on the wall. Usually when February rolled around he was elated, but this year was different. He was severely depressed.

The reason for his depression was a familiar one. Four years of drought and depressed crop prices, coupled with debt incurred to keep farming, had brought him to the brink of foreclosure. He would not be able to borrow for the seed and fertilizer required to put in the crops in spring, fast approaching. And another year’s forbearance on the mortgage would not be granted, the Land Bank had just advised him by certified letter.

The trial began, and as usual most races ended with a voluntary pickup somewhere between an hour and two — lack of finds or fatigue the usual causes. Then on the fourth day came a morning performance that electrified. The dog, a male pointer call name Bud, scored fourteen finds and scorched the course. His handler, Fred, was a known eccentric with more quirks than one could keep count of. He had a few loyal owners, and a host of enemies. Many other handlers were afraid of him, or jealous of him, or both. He had a reputation for fits of temper when an entry failed to be awarded a placement he felt was due. These often ended in verbal tirades against judges, sponsors, and other handlers or scouts he accused of a dirty trick he felt cost him a placement. He assailed judges for inattention, incompetence, bias.

Everyone had Bud as tops after his race. The other handlers knew it. Bud’s handler Fred was told it by two of his owners who did not own Bud, but Fred did not believe that Bud would be awarded the title though he too saw Bud’s performance as tops.

Fred rode every brace after Bud’s. Rode close behind the judges. Other riders heard him often mumbling to himself or speaking into a recorder. At the start of each day the secretary repeated for the gallery but aimed at Fred an admonition to leave a generous gap behind the judges for scouts to cross through and to allow owners and their families and front riders to ride at the head of the gallery. Fred ignored these admonitions.

Then the next to last brace ran. A female pointer named Kate laid down a ten find three hours. Her location on some were not perfect, her range was not as great or as sweeping as Bud’s had been. Few in the gallery thought Kate’s performance had topped Bud’s.

When the last brace had run next morning, ending in the pick up of both dogs at two hours, the judges and the secretary turned their mounts over to marshals and climbed into a waiting Plantation vehicle for the ride to the manor house. On the ride in the senior judge told the secretary to get word out that at 2:00 p.m. a runoff between Bud and Kate would commence on the afternoon course. The other two judges were shocked. They were prepared to announce Bud the winner.

When they reached the manor house and were away from the secretary they questioned the senior judge sharply. What right had he to announce a runoff without consulting them? He responded he had the right as senior judge by long custom. The junior judges protested, but did not countermand Fred’s order to the secretary.

At 2:00 p.m. Kate and Bud were on the line. “Let ‘em go,” the senior judge said. The dogs streaked away. The handlers sang. The judges and gallery of three hundred followed in silence, only the rattle of bit chains and the clomp of hooves blended with the distant songs of the handlers.

At thirty minutes both dogs were out of pocket. The judges halted. Five minutes later the judges huddled away from the gallery. They sent marshals for the handlers. “You have twenty minutes to show us your dogs,” the senior judge said to the two desparate handlers. The handlers exchanged mounts with their dogs’ owners and cantered away.

Ten minutes later Kate’s handler blew his whistle three times and appeared at the front with Kate at heel, then cast her forward on the left edge. When the twenty minutes expired Bud was declared out of judgment and Kate was named National Champion.

When Bud’s handler took his Garmin from a judge it showed Bud on point a hundred yards from where he’d last been seen, buried in brush with his birds still huddled ten yards before him. Kate had not been seen pointed during her callback time.

* * * * *

The senior judge left the Ames Plantation with his mortgage held by a new owner who had granted a five year moratorium on payments of interest and principal. He also had in hand a commitment for loans for seed and fertilizer and chemicals plus fuel. The new lender was Kate’s owner, who had long wanted to own the bragging rights on a National Champion. Neither man left with his self respect. But neither had arrived with it either.

* * * * *

Four Setter watercolors by Edmund Henry Osthaus